Jackson Hole, WY…The Global Financial Crisis and Great Recession posed daunting new challenges for central banks around the world and spurred innovations in the design, implementation, and communication of monetary policy. With the U.S. economy now nearing the Federal Reserve’s statutory goals of maximum employment and price stability, this conference provides a timely opportunity to consider how the lessons we learned are likely to influence the conduct of monetary policy in the future.

The theme of the conference, “Designing Resilient Monetary Policy Frameworks for the Future,” encompasses many aspects of monetary policy, from the nitty-gritty details of implementing policy in financial markets to broader questions about how policy affects the economy. Within the operational realm, key choices include the selection of policy instruments, the specific markets in which the central bank participates, and the size and structure of the central bank’s balance sheet. These topics are of great importance to the Federal Reserve. As noted in the minutes of last month’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, we are studying many issues related to policy implementation, research which ultimately will inform the FOMC’s views on how to most effectively conduct monetary policy in the years ahead. I expect that the work discussed at this conference will make valuable contributions to the understanding of many of these important issues.

My focus today will be the policy tools that are needed to ensure that we have a resilient monetary policy framework. In particular, I will focus on whether our existing tools are adequate to respond to future economic downturns. As I will argue, one lesson from the crisis is that our pre-crisis toolkit was inadequate to address the range of economic circumstances that we faced. Looking ahead, we will likely need to retain many of the monetary policy tools that were developed to promote recovery from the crisis. In addition, policymakers inside and outside the Fed may wish at some point to consider additional options to secure a strong and resilient economy. But before I turn to these longer-run issues, I would like to offer a few remarks on the near-term outlook for the U.S. economy and the potential implications for monetary policy.

Current Economic Situation and Outlook

U.S. economic activity continues to expand, led by solid growth in household spending. But business investment remains soft and subdued foreign demand and the appreciation of the dollar since mid-2014 continue to restrain exports. While economic growth has not been rapid, it has been sufficient to generate further improvement in the labor market. Smoothing through the monthly ups and downs, job gains averaged 190,000 per month over the past three months. Although the unemployment rate has remained fairly steady this year, near 5 percent, broader measures of labor utilization have improved. Inflation has continued to run below the FOMC’s objective of 2 percent, reflecting in part the transitory effects of earlier declines in energy and import prices.

Looking ahead, the FOMC expects moderate growth in real gross domestic product (GDP), additional strengthening in the labor market, and inflation rising to 2 percent over the next few years. Based on this economic outlook, the FOMC continues to anticipate that gradual increases in the federal funds rate will be appropriate over time to achieve and sustain employment and inflation near our statutory objectives. Indeed, in light of the continued solid performance of the labor market and our outlook for economic activity and inflation, I believe the case for an increase in the federal funds rate has strengthened in recent months. Of course, our decisions always depend on the degree to which incoming data continues to confirm the Committee’s outlook.

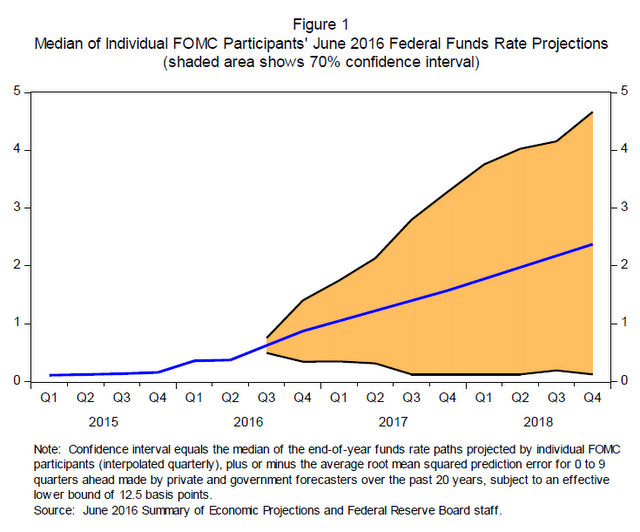

And, as ever, the economic outlook is uncertain, and so monetary policy is not on a preset course. Our ability to predict how the federal funds rate will evolve over time is quite limited because monetary policy will need to respond to whatever disturbances may buffet the economy. In addition, the level of short-term interest rates consistent with the dual mandate varies over time in response to shifts in underlying economic conditions that are often evident only in hindsight. For these reasons, the range of reasonably likely outcomes for the federal funds rate is quite wide–a point illustrated byfigure 1 in your handout. The line in the center is the median path for the federal funds rate based on the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections in June.1 The shaded region, which is based on the historical accuracy of private and government forecasters, shows a 70 percent probability that the federal funds rate will be between 0 and 3-1/4 percent at the end of next year and between 0 and 4-1/2 percent at the end of 2018.2The reason for the wide range is that the economy is frequently buffeted by shocks and thus rarely evolves as predicted. When shocks occur and the economic outlook changes, monetary policy needs to adjust. What we do know, however, is that we want a policy toolkit that will allow us to respond to a wide range of possible conditions.

The Pre-Crisis Toolkit

Prior to the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy toolkit was simple but effective in the circumstances that then prevailed. Our main tool consisted of open market operations to manage the amount of reserve balances available to the banking sector.3 These operations, in turn, influenced the interest rate in the federal funds market, where banks experiencing reserve shortfalls could borrow from banks with excess reserves. Before the onset of the crisis, the volume of reserves was generally small–only about $45 billion or so.4 Thus, even small open market operations could have a significant effect on the federal funds rate. Changes in the federal funds rate would then be transmitted to other short-term interest rates, affecting longer-term interest rates and overall financial conditions and hence inflation and economic activity. This simple, light-touch system allowed the Federal Reserve to operate with a relatively small balance sheet–less than $1 trillion before the crisis–the size of which was largely determined by the need to supply enough U.S. currency to meet demand.5

The global financial crisis revealed two main shortcomings of this simple toolkit. The first was an inability to control the federal funds rate once reserves were no longer relatively scarce. Starting in late 2007, faced with acute financial market distress, the Federal Reserve created programs to keep credit flowing to households and businesses.6 The loans extended under those programs helped stabilize the financial system. But the additional reserves created by these programs, if left unchecked, would have pushed down the federal funds rate, driving it well below the FOMC’s target. To prevent such an outcome, the Federal Reserve took several steps to offset (or sterilize) the effect of its liquidity and credit operations on reserves.7 By the fall of 2008, however, the reserve effects of our liquidity and credit programs threatened to become too large to sterilize via asset sales and other existing tools. Without sufficient sterilization capacity, the quantity of reserves increased to a point that the Federal Reserve had difficulty maintaining effective control over the federal funds rate.

Of course, by the end of 2008, stabilizing the federal funds rate at a level materially above zero was not an immediate concern because the economy clearly needed very low short-term interest rates. Faced with a steep rise in unemployment and declining inflation, the FOMC lowered its target for the federal funds rate to near zero, a reduction of roughly 5 percentage points over the previous year and a half. Nonetheless, a variety of policy benchmarks would, at least in hindsight, have called for pushing the federal funds rate well below zero during the economic downturn.8 That doing so was impossible highlights the second serious limitation of our pre-crisis policy toolkit: its inability to generate substantially more accommodation than could be provided by a near-zero federal funds rate.

Our Expanded Toolkit

To address the challenges posed by the financial crisis and the subsequent severe recession and slow recovery, the Federal Reserve significantly expanded its monetary policy toolkit. In 2006, the Congress had approved plans to allow the Fed, beginning in 2011, to pay interest on banks’ reserve balances.9 In the fall of 2008, the Congress moved up the effective date of this authority to October 2008. That authority was essential. Paying interest on reserve balances enables the Fed to break the strong link between the quantity of reserves and the level of the federal funds rate and, in turn, allows the Federal Reserve to control short-term interest rates when reserves are plentiful. In particular, once economic conditions warrant a higher level for market interest rates, the Federal Reserve could raise the interest rate paid on excess reserves–the IOER rate. A higher IOER rate encourages banks to raise the interest rates they charge, putting upward pressure on market interest rates regardless of the level of reserves in the banking sector.

While adjusting the IOER rate is an effective way to move market interest rates when reserves are plentiful, federal funds have generally traded below this rate. This relative softness of the federal funds rate reflects, in part, the fact that only depository institutions can earn the IOER rate. To put a more effective floor under short-term interest rates, the Federal Reserve created supplementary tools to be used as needed. For instance, the overnight reverse repurchase agreement (ON RRP) facility is available to a variety of counterparties, including eligible money market funds, government-sponsored enterprises, broker-dealers, and depository institutions. Through it, eligible counterparties may invest funds overnight with the Federal Reserve at a rate determined by the FOMC. Similar to the payment of IOER, the ON RRP facility discourages participating institutions from lending at a rate substantially below that offered by the Fed.10

Our current toolkit proved effective last December. In an environment of superabundant reserves, the FOMC raised the effective federal funds rate–that is, the weighted average rate on federal funds transactions among participants in that market–by the desired amount, and we have since maintained the federal funds rate in its target range.

Two other major additions to the Fed’s toolkit were large-scale asset purchases and increasingly explicit forward guidance.11 Both were used to provide additional monetary policy accommodation after short-term interest rates fell close to zero. Our purchases of Treasury and mortgage-related securities in the open market pushed down longer-term borrowing rates for millions of American families and businesses. Extended forward rate guidance–announcing that we intended to keep short-term interest rates lower for longer than might have otherwise been expected–also put significant downward pressure on longer-term borrowing rates, as did guidance regarding the size and scope of our asset purchases.

In light of the slowness of the economic recovery, some have questioned the effectiveness of asset purchases and extended forward rate guidance. But this criticism fails to consider the unusual headwinds the economy faced after the crisis. Those headwinds included substantial household and business deleveraging, unfavorable demand shocks from abroad, a period of contractionary fiscal policy, and unusually tight credit, especially for housing. Studies have found that our asset purchases and extended forward rate guidance put appreciable downward pressure on long-term interest rates and, as a result, helped spur growth in demand for goods and services, lower the unemployment rate, and prevent inflation from falling further below our 2 percent objective.12

Two of the Fed’s most important new tools–our authority to pay interest on excess reserves and our asset purchases–interacted importantly. Without IOER authority, the Federal Reserve would have been reluctant to buy as many assets as it did because of the longer-run implications for controlling the stance of monetary policy. While we were buying assets aggressively to help bring the U.S. economy out of a severe recession, we also had to keep in mind whether and how we would be able to remove monetary policy accommodation when appropriate. That issue was particularly relevant because we fund our asset purchases through the creation of reserves, and those additional reserves would have made it ever more difficult for the pre-crisis toolkit to raise short-term interest rates when needed.

The FOMC considered removing accommodation by first reducing our asset holdings (including through asset sales) and raising the federal funds rate only after our balance sheet had contracted substantially. But we decided against this approach because our ability to predict the effects of changes in the balance sheet on the economy is less than that associated with changes in the federal funds rate. Excessive inflationary pressures could arise if assets were sold too slowly. Conversely, financial markets and the economy could potentially be destabilized if assets were sold too aggressively. Indeed, the so-called taper tantrum of 2013 illustrates the difficulty of predicting financial market reactions to announcements about the balance sheet. Given the uncertainty and potential costs associated with large-scale asset sales, the FOMC instead decided to begin removing monetary policy accommodation primarily by adjusting short-term interest rates rather than by actively managing its asset holdings.13 That strategy–raising short-term interest rates once the recovery was sufficiently advanced while maintaining a relatively large balance sheet and plentiful bank reserves–depended on our ability to pay interest on excess reserves.

Where Do We Go from Here?

What does the future hold for the Fed’s toolkit? For starters, our ability to use interest on reserves is likely to play a key role for years to come. In part, this reflects the outlook for our balance sheet over the next few years. As the FOMC has noted in its recent statements, at some point after the process of raising the federal funds rate is well under way, we will cease or phase out reinvesting repayments of principal from our securities holdings. Once we stop reinvestment, it should take several years for our asset holdings–and the bank reserves used to finance them–to passively decline to a more normal level. But even after the volume of reserves falls substantially, IOER will still be important as a contingency tool, because we may need to purchase assets during future recessions to supplement conventional interest rate reductions.14 Forecasts now show the federal funds rate settling at about 3 percent in the longer run.15 In contrast, the federal funds rate averaged more than 7 percent between 1965 and 2000. Thus, we expect to have less scope for interest rate cuts than we have had historically.

In part, current expectations for a low future federal funds rate reflect the FOMC’s success in stabilizing inflation at around 2 percent–a rate much lower than rates that prevailed during the 1970s and 1980s. Another key factor is the marked decline over the past decade, both here and abroad, in the long-run neutral real rate of interest–that is, the inflation-adjusted short-term interest rate consistent with keeping output at its potential on average over time.16 Several developments could have contributed to this apparent decline, including slower growth in the working-age populations of many countries, smaller productivity gains in the advanced economies, a decreased propensity to spend in the wake of the financial crises around the world since the late 1990s, and perhaps a paucity of attractive capital projects worldwide.17 Although these factors may help explain why bond yields have fallen to such low levels here and abroad, our understanding of the forces driving long-run trends in interest rates is nevertheless limited, and thus all predictions in this area are highly uncertain.18

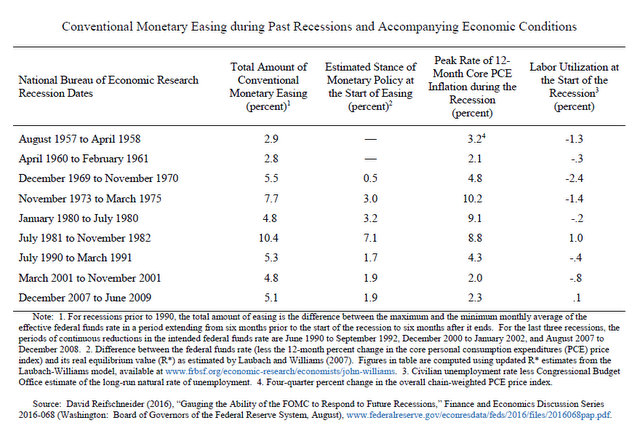

Would an average federal funds rate of about 3 percent impair the Fed’s ability to fight recessions? Based on the FOMC’s behavior in past recessions, one might think that such a low interest rate could substantially impair policy effectiveness. As shown in the first column of the table in the handout, during the past nine recessions, the FOMC cut the federal funds rate by amounts ranging from about 3 percentage points to more than 10 percentage points. On average, the FOMC reduced rates by about 5-1/2 percentage points, which seems to suggest that the FOMC would face a shortfall of about 2-1/2 percentage points for dealing with an average-sized recession. But this simple comparison exaggerates the limitations on policy created by the zero lower bound. As shown in the second column, the federal funds rate at the start of the past seven recessions was appreciably above the level consistent with the economy operating at potential in the longer run. In most cases, this tighter-than-normal stance of policy before the recession appears to have reflected some combination of initially higher-than-normal labor utilization and elevated inflation pressures. As a result, a large portion of the rate cuts that subsequently occurred during these recessions represented the undoing of the earlier tight stance of monetary policy. Of course, this situation could occur again in the future. But if it did, the federal funds rate at the onset of the recession would be well above its normal level, and the FOMC would be able to cut short-term interest rates by substantially more than 3 percentage points.

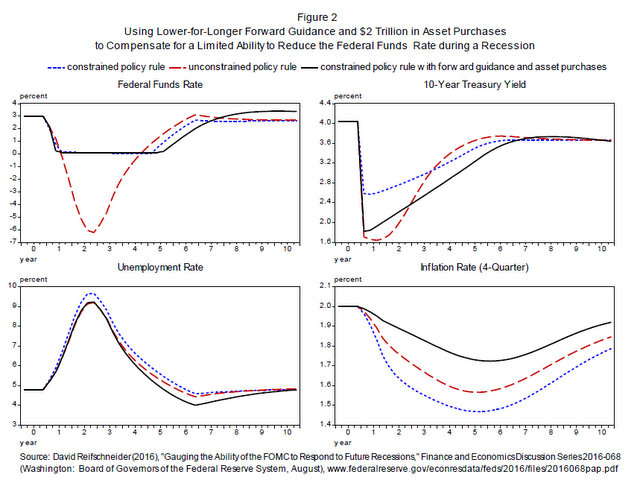

A recent paper takes a different approach to assessing the FOMC’s ability to respond to future recessions by using simulations of the FRB/US model.19 This analysis begins by asking how the economy would respond to a set of highly adverse shocks if policymakers followed a fairly aggressive policy rule, hypothetically assuming that they can cut the federal funds rate without limit.20 It then imposes the zero lower bound and asks whether some combination of forward guidance and asset purchases would be sufficient to generate economic conditions at least as good as those that occur under the hypothetical unconstrained policy. In general, the study concludes that, even if the average level of the federal funds rate in the future is only 3 percent, these new tools should be sufficient unless the recession were to be unusually severe and persistent.

Figure 2 in your handout illustrates this point. It shows simulated paths for interest rates, the unemployment rate, and inflation under three different monetary policy responses–the aggressive rule in the absence of the zero lower bound constraint, the constrained aggressive rule, and the constrained aggressive rule combined with $2 trillion in asset purchases and guidance that the federal funds rate will depart from the rule by staying lower for longer.21 As the blue dashed line shows, the federal funds rate would fall far below zero if policy were unconstrained, thereby causing long-term interest rates to fall sharply. But despite the lower bound, asset purchases and forward guidance can push long-term interest rates even lower on average than in the unconstrained case (especially when adjusted for inflation) by reducing term premiums and increasing the downward pressure on the expected average value of future short-term interest rates. Thus, the use of such tools could result in even better outcomes for unemployment and inflation on average.

Of course, this analysis could be too optimistic. For one, the FRB/US simulations may overstate the effectiveness of forward guidance and asset purchases, particularly in an environment where long-term interest rates are also likely to be unusually low.22 In addition, policymakers could have less ability to cut short-term interest rates in the future than the simulations assume. By some calculations, the real neutral rate is currently close to zero, and it could remain at this low level if we were to continue to see slow productivity growth and high global saving.23 If so, then the average level of the nominal federal funds rate down the road might turn out to be only 2 percent, implying that asset purchases and forward guidance might have to be pushed to extremes to compensate.24 Moreover, relying too heavily on these nontraditional tools could have unintended consequences. For example, if future policymakers responded to a severe recession by announcing their intention to keep the federal funds rate near zero for a very long time after the economy had substantially recovered and followed through on that guidance, then they might inadvertently encourage excessive risk-taking and so undermine financial stability.

Finally, the simulation analysis certainly overstates the FOMC’s current ability to respond to a recession, given that there is little scope to cut the federal funds rate at the moment. But that does not mean that the Federal Reserve would be unable to provide appreciable accommodation should the ongoing expansion falter in the near term. In addition to taking the federal funds rate back down to nearly zero, the FOMC could resume asset purchases and announce its intention to keep the federal funds rate at this level until conditions had improved markedly–although with long-term interest rates already quite low, the net stimulus that would result might be somewhat reduced.

Despite these caveats, I expect that forward guidance and asset purchases will remain important components of the Fed’s policy toolkit. In addition, it is critical that the Federal Reserve and other supervisory agencies continue to do all they can to ensure a strong and resilient financial system. That said, these tools are not a panacea, and future policymakers could find that they are not adequate to deal with deep and prolonged economic downturns. For these reasons, policymakers and society more broadly may want to explore additional options for helping to foster a strong economy.

On the monetary policy side, future policymakers might choose to consider some additional tools that have been employed by other central banks, though adding them to our toolkit would require a very careful weighing of costs and benefits and, in some cases, could require legislation. For example, future policymakers may wish to explore the possibility of purchasing a broader range of assets. Beyond that, some observers have suggested raising the FOMC’s 2 percent inflation objective or implementing policy through alternative monetary policy frameworks, such as price-level or nominal GDP targeting. I should stress, however, that the FOMC is not actively considering these additional tools and policy frameworks, although they are important subjects for research.

Beyond monetary policy, fiscal policy has traditionally played an important role in dealing with severe economic downturns. A wide range of possible fiscal policy tools and approaches could enhance the cyclical stability of the economy.25 For example, steps could be taken to increase the effectiveness of the automatic stabilizers, and some economists have proposed that greater fiscal support could be usefully provided to state and local governments during recessions. As always, it would be important to ensure that any fiscal policy changes did not compromise long-run fiscal sustainability.

Finally, and most ambitiously, as a society we should explore ways to raise productivity growth. Stronger productivity growth would tend to raise the average level of interest rates and therefore would provide the Federal Reserve with greater scope to ease monetary policy in the event of a recession. But more importantly, stronger productivity growth would enhance Americans’ living standards. Though outside the narrow field of monetary policy, many possibilities in this arena are worth considering, including improving our educational system and investing more in worker training; promoting capital investment and research spending, both private and public; and looking for ways to reduce regulatory burdens while protecting important economic, financial, and social goals.

Conclusion

Although fiscal policies and structural reforms can play an important role in strengthening the U.S. economy, my primary message today is that I expect monetary policy will continue to play a vital part in promoting a stable and healthy economy. New policy tools, which helped the Federal Reserve respond to the financial crisis and Great Recession, are likely to remain useful in dealing with future downturns. Additional tools may be needed and will be the subject of research and debate. But even if average interest rates remain lower than in the past, I believe that monetary policy will, under most conditions, be able to respond effectively.

1. The June 2016 Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) is an addendum to the minutes of the June 2016 FOMC meeting and is available on the Board’s website atwww.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcminutes20160615.pdf. Return to text

2. The confidence interval equals (subject to a lower bound of 12.5 basis points) the median SEP path for the federal funds rate plus or minus average root mean squared prediction errors (RMSPEs) of the three-month Treasury bill rate, for horizons from zero to nine quarters ahead, based on forecast errors made over the past 20 years. Average RMSPEs are calculated as the mean of the RMSPEs of the following forecasters, subject to availability for the horizon in question: the Federal Reserve Board staff (Greenbook/Tealbook), the Administration, the Congressional Budget Office, the Blue Chip consensus forecast, and the Survey of Professional Forecasters. Differences in predictive accuracy among these forecasters are not statistically significant. For more information on the general methodology used to construct confidence intervals using historical forecasting errors, see David Reifschneider and Peter Tulip (2007), “Gauging the Uncertainty of the Economic Outlook from Historical Forecasting Errors (PDF),” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2007-60 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, November). Return to text

3. Open market operations at the time were primarily repurchase agreements based on Treasury securities, with primary dealers as counterparties. Return to text

4. Reserves of depository institutions include vault cash and balances maintained with Federal Reserve Banks. Excess reserves are the reserves held over and above required reserves. See the Board’s webpage “Reserve Requirements” atwww.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/reservereq.htm. Return to text

5. Prior to the financial crisis, the size of the Fed’s balance sheet was about $900 billion. Assets consisted almost entirely of Treasury securities. Liabilities included currency held by the public and a relatively small volume of reserve balances. For more on the Fed’s balance sheet, seewww.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst_fedsbalancesheet.htm. Return to text

6. For information on the Federal Reserve’s credit and liquidity programs that were implemented in response to the financial crisis, seewww.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst_crisisresponse.htm on the Board’s website.Return to text

7. Reserves were initially taken out of the banking system by not reinvesting principal payments from maturing securities and later by selling portions of securities holdings. In September 2008, the Department of the Treasury announced the temporary Supplementary Financing Program, in which the proceeds of a series of Treasury bill auctions, separate from Treasury’s routine borrowing, were maintained in an account at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The funds in this account served to drain reserves from the banking system. Return to text

8. Consider the following policy rule: R(t) = R* + p(t) + 0.5[p(t)-p*]-2.0[U(t)-U*], where R is the federal funds rate, R* is the longer-run normal value of the federal funds rate adjusted for inflation, p is the four-quarter moving average of core PCE inflation, p* is the FOMC’s target for inflation (2 percent), U is the unemployment rate, and U* is the longer-run normal rate of unemployment. Based on the medians of FOMC participants’ latest longer-run projections, R* is approximately 1 percent and U* is about 4.8 percent. Accordingly, with the unemployment rate climbing to 10 percent and core PCE inflation falling to 1 percent in 2009, this rule would have prescribed lowering the federal funds rate to minus 9 percent at the depths of the recession. In contrast, the standard Taylor rule, which is half as responsive to movements in resource utilization, would have prescribed lowering the federal funds rate to minus 3-3/4 percent using the same estimates for R* and U*. The more aggressive rule does a reasonably good job of accounting for movements in the federal funds rate in the decade prior to its falling to its effective lower bound in late 2008, see David Reifschneider (2016), “Gauging the Ability of the FOMC to Respond to Future Recessions (PDF),” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2016-068 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, August). For more information on the standard Taylor rule, see John B. Taylor (1993), “Discretion versus Policy Rules in Practice,” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, vol. 39 (December), pp. 195-214. Return to text

9. Paying interest on reserves is a tool commonly used by central banks, including the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, and the European Central Bank. Return to text

10. Other tools that could help strengthen the floor under short-term interest rates but are not currently in use include the Term Deposit Facility and term reverse repurchase agreements. Return to text

11. Prior to the crisis, the Fed occasionally used forward guidance pertaining to the likely future path of interest rates, but that guidance was usually confined to a relatively short time frame. Return to text

12. See, for instance, Joseph Gagnon, Matthew Raskin, Julie Remache, and Brian Sack (2011), “The Financial Market Effects of the Federal Reserve’s Large-Scale Asset Purchases,” ![]() International Journal of Central Banking, vol. 7 (March), pp. 3-43; and Stefania D’Amico, William English, David López-Salido, and Edward Nelson (2012), “The Federal Reserve’s Large-Scale Asset Purchase Programmes: Rationale and Effects,”Economic Journal, vol. 122 (November), pp. F415-46. Moreover, the Federal Reserve’s forward guidance and asset purchase policies have been estimated to have helped lower unemployment and boost inflation; see Eric M. Engen, Thomas Laubach, and David Reifschneider (2015), “The Macroeconomic Effects of the Federal Reserve’s Unconventional Monetary Policies,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2015-005 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, January). Return to text

International Journal of Central Banking, vol. 7 (March), pp. 3-43; and Stefania D’Amico, William English, David López-Salido, and Edward Nelson (2012), “The Federal Reserve’s Large-Scale Asset Purchase Programmes: Rationale and Effects,”Economic Journal, vol. 122 (November), pp. F415-46. Moreover, the Federal Reserve’s forward guidance and asset purchase policies have been estimated to have helped lower unemployment and boost inflation; see Eric M. Engen, Thomas Laubach, and David Reifschneider (2015), “The Macroeconomic Effects of the Federal Reserve’s Unconventional Monetary Policies,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2015-005 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, January). Return to text

13. The FOMC’s “Policy Normalization Principles and Plans” call for reducing the Federal Reserve’s securities holdings in a “gradual and predictable manner primarily by ceasing to reinvest repayments of principal on securities held in the [System Open Market Account]” (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2014), “Federal Reserve Issues FOMC Statement on Policy Normalization Principles and Plans,” press release, September 17, second bullet). Consistent with those plans, the Federal Open Market Committee anticipates that it will maintain its current reinvestment strategy “until normalization of the level of the federal funds rate is well under way” (for instance, see Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2015), “Federal Reserve Issues FOMC Statement,” press release, December 16, paragraph 5. Return to text

14. If the FOMC were to again increase the size of the balance sheet markedly in response to a future recession, then the ability to pay interest on reserves could be critical during the subsequent recovery period to help control short-term interest rates while the balance sheet remains elevated. Beyond this motivation for retaining IOER, the ability to pay interest on reserves could also be important to the operation of any special liquidity and credit facilities that might be created to deal with systemic disruptions to the financial system during a future emergency. In particular, such facilities could significantly expand the supply of reserves, which would be problematic if the FOMC wished to keep short-term interest rates from falling to zero. Return to text

15. In the Blue Chip Financial Indicators survey released on June 1, 2016, the consensus forecast for the longer-run level of the federal funds rate was 3.2 percent. FOMC participants in June 2016 generally anticipated a slightly lower longer-run level, in that the median of their individual forecasts was 3 percent (see table 1 of the June 2016 SEP, available at www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcminutes20160615ep.htm). The latest long-run forecast from the Administration (www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2016/assets/16msr.pdf) is also close to 3 percent, as was the projection made by the Congressional Budget Office earlier in the year (see www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget_economic_data). Return to text

16. Updated estimates from the model developed by Laubach and Williams (2003) indicate that the real long-run neutral or “equilibrium” short-term interest rate in the United States is currently about 2-1/2 percentage points lower than it was on average in the 1980s and 1990s (see Thomas Laubach and John C. Williams (2003), “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest,” Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 85 (November), pp. 1063-70; updated estimates are available at www.frbsf.org/economic-research/economists/john-williams/Laubach_Williams_updated_estimates.xlsx.) ![]() In addition, Holston, Laubach, and Williams (2016) find significant but somewhat smaller declines in equilibrium rates for the euro area, Canada, and the United Kingdom (see Kathryn Holston, Thomas Laubach, and John C. Williams (2016), “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants,” Working Paper 2016-11 (San Francisco: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, June), www.frbsf.org/economic-research/files/wp2016-11.pdf).

In addition, Holston, Laubach, and Williams (2016) find significant but somewhat smaller declines in equilibrium rates for the euro area, Canada, and the United Kingdom (see Kathryn Holston, Thomas Laubach, and John C. Williams (2016), “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants,” Working Paper 2016-11 (San Francisco: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, June), www.frbsf.org/economic-research/files/wp2016-11.pdf). ![]() Return to text

Return to text

17. For a discussion of the possible role played by these factors in explaining the current low level of interest rates in the United States and other advanced economies, see Lawrence H. Summers (2014), “U.S. Economic Prospects: Secular Stagnation, Hysteresis, and the Zero Lower Bound,” Business Economics, vol. 49 (April), pp. 65-73; Robert J. Gordon (2014), “The Demise of U.S. Economic Growth: Restatement, Rebuttal, and Reflections,” ![]() NBER Working Paper 19895 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, February); and Ben S. Bernanke (2015), “Why Are Interest Rates So Low, Part 2: Secular Stagnation,”

NBER Working Paper 19895 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, February); and Ben S. Bernanke (2015), “Why Are Interest Rates So Low, Part 2: Secular Stagnation,” ![]() Ben Bernanke’s Blog, blog post (Washington: Brookings Institution, March 31). Return to text

Ben Bernanke’s Blog, blog post (Washington: Brookings Institution, March 31). Return to text

18. For example, see James D. Hamilton, Ethan S. Harris, Jan Hatzius, and Kenneth D. West (2015), “The Equilibrium Real Funds Rate: Past, Present, and Future,” ![]() NBER Working Paper 21476 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, August); and Olivier Blanchard (2016), “Three Remarks on the U.S. Treasury Yield Curve,”

NBER Working Paper 21476 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, August); and Olivier Blanchard (2016), “Three Remarks on the U.S. Treasury Yield Curve,” ![]() Realtime Economic Issues Watch (Washington: Peterson Institute for International Economics, June 22). Return to text

Realtime Economic Issues Watch (Washington: Peterson Institute for International Economics, June 22). Return to text

19. FRB/US model simulations have several advantages for analyzing this issue. For one, the model’s structure allows the public’s expectations for interest rates, inflation, and other factors to take full account of the implications of the effective lower bound on nominal interest rates, changes in future monetary policy as signaled by forward guidance, and asset purchases. In addition, the model incorporates the low responsiveness of inflation to movements in resource utilization seen in recent years as well as the effects of asset purchases on term premiums, and thus a variety of longer-term interest rates, equity prices, and the foreign exchange value of the dollar. For a further discussion about the advantages (and possible disadvantages) of using the FRB/US model to study this issue, see Reifschneider, “Gauging the Ability of the FOMC to Respond to Future Recessions,” in note 8. Return to text

20. The aggressive rule is R(t) = 1.0 + p(t) + 0.5 [p(t)-2] – 2.0 [4.8 – U(t)], where R is the federal funds rate, p is the four-quarter moving average of core PCE inflation, and U is the unemployment rate. Note that baseline values of the equilibrium real rate, the natural rate of unemployment, and the target rate of inflation used in the simulation analysis–1.0 percent, 4.8 percent, and 2.0 percent, respectively–are consistent with the medians of the latest long-run projections of individual FOMC participants. As discussed by Taylor (1999), this rule appears to do a good job in stabilizing real activity and inflation in a wide range of economic models (see John B. Taylor (1999), “Introduction,” in John B. Taylor, ed., Monetary Policy Rules (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), pp. 1-14). Return to text

21. The forward guidance is provided at the start of the recession and has three components. First, the federal funds rate will be lowered to zero more quickly than prescribed by the rule. Second, the federal funds rate will remain at zero as long as the unemployment rate is greater than 5 percent. And, finally, that after the initial increase in the federal funds rate, policymakers will proceed gradually in returning to the prescriptions of the policy rule. Return to text

22. As shown in figure 2, the 10-year Treasury yield in the simulation starts out at just over 4 percent, well below its level pre-crisis, suggesting that there may be less room to push down long-term interest rates in the future than in the past. Another potential source of overstatement could be the FRB/US assumption that changes in long-term interest rates, whether driven by shifts in term premiums or shifts in the expected path of short-term interest rates, have the same influence on real activity, as there is some empirical evidence that the estimated sensitivity of spending to movements in term premiums alone may be relatively small; see Michael T. Kiley (2014), “The Aggregate Demand Effects of Short- and Long-Term Interest Rates,” ![]() International Journal of Central Banking, vol. 10 (December), pp. 69-104. On the other hand, the effectiveness of forward guidance in the FRB/US model is materially less than it is in some other models, implying that the FRB/US simulation results could potentially understate the stimulus provided by the announcement of a lower-for-longer policy. See Hess Chung (2015), “The Effects of Forward Guidance in Three Macro Models,” FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, February 26). Return to text

International Journal of Central Banking, vol. 10 (December), pp. 69-104. On the other hand, the effectiveness of forward guidance in the FRB/US model is materially less than it is in some other models, implying that the FRB/US simulation results could potentially understate the stimulus provided by the announcement of a lower-for-longer policy. See Hess Chung (2015), “The Effects of Forward Guidance in Three Macro Models,” FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, February 26). Return to text

23. In principle, the federal funds rate in the longer run could also turn out to be lower than currently predicted if inflation were to remain persistently below 2 percent. However, because a higher rate of inflation can arguably be achieved over time through a sufficiently tight labor market, this risk seems low to me as long as the Federal Reserve is committed to achieving its inflation objective. Return to text

24. In the simulations reported by Reifschneider, “Gauging the Ability of the FOMC to Respond to Future Recessions,” in note 8, overcoming the effects of the zero lower bound during a severe recession would require about $4 trillion in asset purchases and pledging to stay low for even longer if the average future level of the federal funds rate is only 2 percent. Return to text

25. For further discussion of ways to enhance the effectiveness of fiscal policy in stabilizing the economy, see Xavier Debrun and Radhicka Kapoor (2010), “Fiscal Policy and Macroeconomic Stability: Automatic Stabilizers Work, Always and Everywhere (PDF),” ![]() IMF Working Paper WP/10/111 (Washington: International Monetary Fund, May); Antonio Fatás and Ilian Mihov (2012), “Fiscal Policy as a Stabilization Tool,” B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics, vol. 12 (October), pp. 1-66; International Monetary Fund (2015), “Can Fiscal Policy Stabilize Output? (PDF)”

IMF Working Paper WP/10/111 (Washington: International Monetary Fund, May); Antonio Fatás and Ilian Mihov (2012), “Fiscal Policy as a Stabilization Tool,” B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics, vol. 12 (October), pp. 1-66; International Monetary Fund (2015), “Can Fiscal Policy Stabilize Output? (PDF)” ![]() chapter 2 in Fiscal Monitor(Washington: IMF, April), pp. 21-48; and Alisdair McKay and Ricardo Reis (2016), “The Role of Automatic Stabilizers in the U.S. Business Cycle,” Econometrica, vol. 84 (January), pp. 141-94. Return to text

chapter 2 in Fiscal Monitor(Washington: IMF, April), pp. 21-48; and Alisdair McKay and Ricardo Reis (2016), “The Role of Automatic Stabilizers in the U.S. Business Cycle,” Econometrica, vol. 84 (January), pp. 141-94. Return to text