Moffett Field, CA…The discovery of a super-Earth-sized planet orbiting a sun-like star brings us closer than ever to finding a twin of our own watery world. But NASA’s Kepler space telescope has captured evidence of other potentially habitable planets amid the sea of stars in the Milky Way galaxy.

To take a brief tour of the more prominent contenders, it helps to zero in on the “habitable zone” around their stars. This is the band of congenial temperatures for planetary orbits — not too close and not too far. Too close and the planet is fried (we’re looking at you, Venus). Too far and it’s in deep freeze. But settle comfortably into the habitable zone, and your planet could have liquid water on its surface — just right. Goldilocks has never been more relevant. Scientists have, in fact, taken to calling this water-friendly region the “Goldilocks zone.”

The zone can be a wide band or a narrow one, and nearer the star or farther, depending on the star’s size and energy output. For small, red-dwarf stars, habitable zone planets might gather close, like marshmallow-roasting campers around the fire. For gigantic, hot stars, the band must retreat to a safer distance.

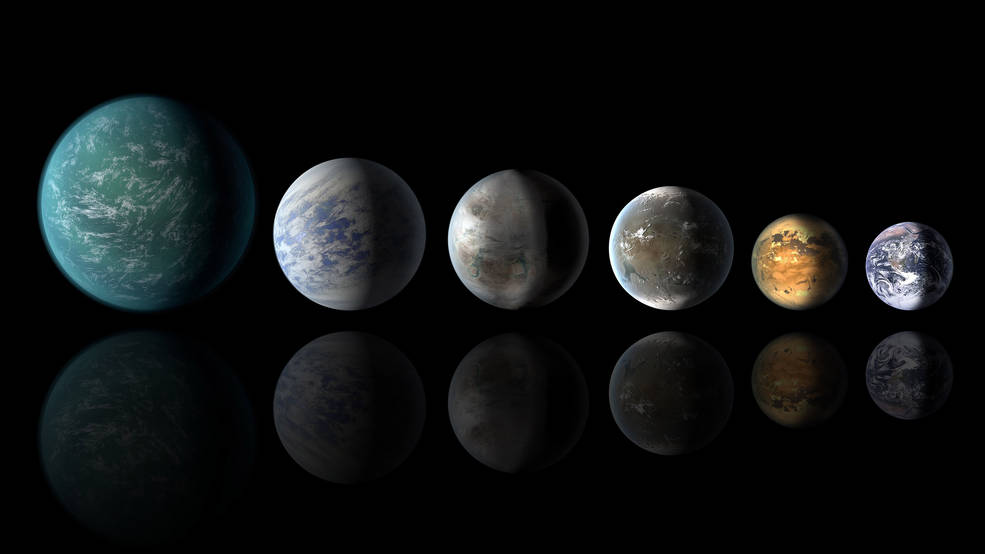

About a dozen habitable zone planets in the Earth-size ballpark have been discovered so far — that is, 10 to 15 planets between one-half and twice the diameter of Earth, depending on how the habitable zone is defined and allowing for uncertainties about some of the planetary sizes.

The new discovery, Kepler-452b, fires the planet hunter’s imagination because it is the most similar to the Earth-sun system found yet: a planet at the right temperature within the habitable zone, and only about one-and-a-half times the diameter of Earth, circling a star very much like our own sun. The planet also has a good chance of being rocky, like Earth, its discoverers say.

Kepler-452b is more similar to Earth than any system previously discovered. And the timing is especially fitting: 2015 marks the 20th anniversary of the first exoplanet confirmed to be in orbit around a typical star.

But several other exoplanet discoveries came nearly as close in their similarity to Earth.

Before this, the planet Kepler-186f held the “most similar” distinction (they get the common moniker, “Kepler,” because they were discovered with the Kepler space telescope). About 500 light-years from Earth, Kepler-186f is no more than 10 percent larger than Earth, and sails through its star’s habitable zone, making its surface potentially watery.

But its 130-day orbit carries it around a red-dwarf star that is much cooler than our sun and only half its size. Thus, the planet is really more like an “Earth cousin,” says Thomas Barclay of the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute at NASA’s Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California, a co-author of the paper announcing the discovery in April 2014.

Kepler-186f gets about one-third the energy from its star that Earth gets from our sun. And that puts it just at the outside edge of the habitable zone. Scientists say that if you were standing on the planet at noon, the light would look about as bright as it does on Earth an hour before sunset.

That doesn’t mean the planet is bereft of life, although it doesn’t mean life exists there, either.

Before Kepler-186f, Kepler-62f was the exoplanet known to be most similar to Earth. Like the new discovery, Kepler-62f is a “super Earth,” about 40 percent larger than our home planet. But, like Kepler-186f, its 267-day orbit also carries it around a star that is cooler and smaller than the sun, some 1,200 light-years away in the constellation Lyra. Still, Kepler-62f does reside in the habitable zone.

Kepler-62f’s discovery was announced in April 2013, about the same time as Kepler-69c, another super Earth — though one that is 70 percent larger than our home planet. That’s the bad news; astronomers are uncertain about the planet’s composition, or just when a “super Earth” becomes so large that it diminishes the chance of finding life on its surface. That also moves it farther than its competitors from the realm of a potential Earth twin. The good news is that Kepler-69c lies in its sun’s habitable zone, with a 242-day orbit reminiscent of our charbroiled sister planet, Venus. Its star is also similar to ours in size with about 80 percent of the sun’s luminosity. Its planetary system is about 2,700 light-years away in the constellation Cygnus.

Kepler-22b also was hailed in its day as the most like Earth. It was the first of the Kepler planets to be found within the habitable zone, and it orbits a star much like our sun. But Kepler-22b is a sumo wrestler among super Earths, about 2.4 times Earth’s size. And no one knows if it is rocky, gaseous or liquid. The planet was detected almost immediately after Kepler began making observations in 2009, and was confirmed in 2011. This planet, which could have a cloudy atmosphere, is 600 light-years away, with a 290-day orbit not unlike Earth’s.

Not all the planets jostling to be most like Earth were discovered using Kepler. A super Earth known as Gliese 667Cc also came to light in 2011, discovered by astronomers combing through data from the European Southern Observatory’s 3.6-meter telescope in Chile. The planet, only 22 light-years away, has a mass at least 4.5 times that of Earth. It orbits a red dwarf in the habitable zone, though closely enough — with a mere 28-day orbit — to make the planet subject to intense flares that could erupt periodically from the star’s surface. Still, its sun is smaller and cooler than ours, and Gliese 667Cc’s orbital distance means it probably receives around 90 percent of the energy we get from the sun. That’s a point in favor of life, if the planet’s atmosphere is something like ours. The planet’s true size and density remain unknown, however, which means it could still turn out to be a gas planet, hostile to life as we know it. And powerful magnetic fluxes also could mean periodic drop-offs in the amount of energy reaching the planet, by as much as 40 percent. These drop-offs could last for months, according to scientists at the University of Oslo’s Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics in Norway.

Deduct two points.

Too big, too uncertain, or circling the wrong kind of star: Shuffle through the catalog of habitable zone planets, and the closest we can come to Earth — at least so far — appears to be the new kid on the interstellar block, Kepler-452b.

NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, manages the Kepler and K2 missions for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, managed Kepler mission development. Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp. operates the flight system with support from the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

JPL is managed by The California Institute of Technology for NASA.

More information about Kepler is online at:

http://www.nasa.gov/kepler

More information about NASA’s planet-hunting efforts is online at:

http://planetquest.jpl.nasa.gov

Testing