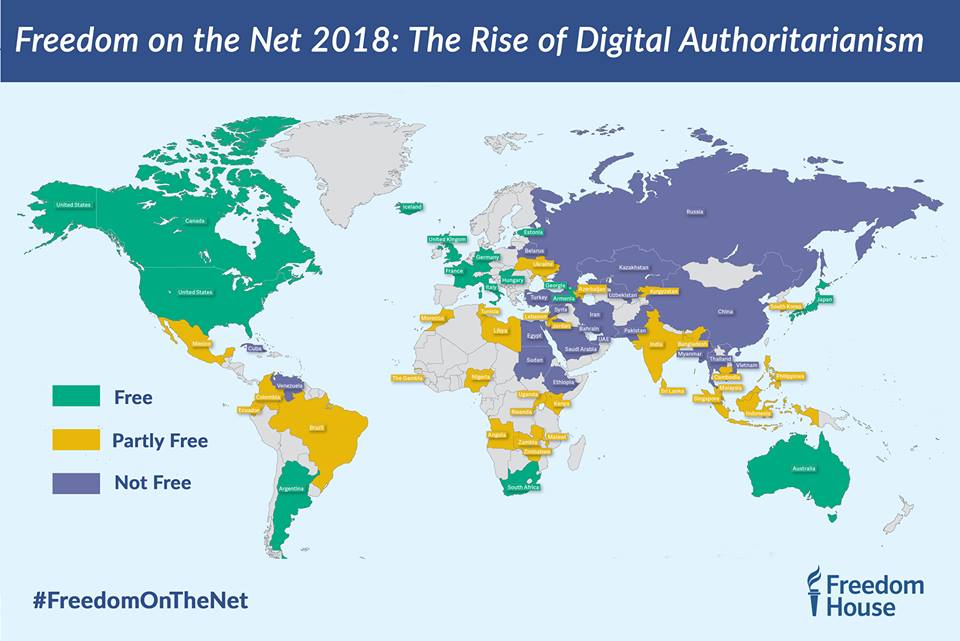

Washington, DC…Governments around the world are tightening control over citizens’ data and using claims of “fake news” to suppress dissent, eroding trust in the internet as well as the foundations of democracy, according to Freedom on the Net 2018: The Rise of Digital Authoritarianism, the latest edition of the annual country-by-country assessment of online freedom, released today by Freedom House. Online propaganda and disinformation have increasingly poisoned the digital sphere, while the unbridled collection of personal data is breaking down traditional notions of privacy. At the same time, China has become more brazen and adept at controlling the internet at home and exporting its techniques to other countries.

These trends led global internet freedom to decline for the eighth consecutive year in 2018.

“Democracies are struggling in the digital age, while China is exporting its model of censorship and surveillance to control information both inside and outside its borders,” said Michael J. Abramowitz, president of Freedom House. “This pattern poses a threat to the open internet and endangers prospects for greater democracy worldwide.”

“The U.S. government and major U.S. tech companies need to take a more proactive role in preventing online manipulation and protecting users’ data,” Abramowitz said. “The current weaknesses in the system have played into the hands of less democratic governments looking to increase their control of the internet.”

Freedom on the Net 2018 assesses internet freedom in 65 countries that account for 87 percent of internet users worldwide. The report focuses on developments that occurred between June 2017 and May 2018, though some more recent events are included.

“This year has proved that the internet can be used to disrupt democracies as surely as it can destabilize dictatorships,” said Adrian Shahbaz, Freedom House’s research director for technology and democracy.

Beijing took steps during the year to remake the world in its techno-dystopian image. Chinese officials have held trainings and seminars on new media or information management with representatives from 36 out of the 65 countries assessed by Freedom on the Net. China also provided telecommunications and surveillance equipment to foreign governments and demanded that international companies abide by its content regulations even when operating abroad.

A proliferation of data leaks has underscored a pressing need to improve protections for users’ information and privacy. Both democracies and authoritarian regimes are instituting changes in the name of data security, but some initiatives actually undermine internet freedom and user privacy by mandating data localization and weakening encryption. In India, a massive data breach affecting 1.1 billion citizens reiterated the need for reforms to the country’s data protection framework, beyond an ineffective government proposal to require that data be stored locally. More promising efforts for data protection resembled the EU’s ambitious but imperfect General Data Protection Regulation, which came into effect in May 2018.

“For democracy to survive the digital age, technology companies, governments, and civil society will have to work together to find real solutions to online manipulation and lack of data privacy,” said Sanja Kelly, Freedom House’s director for internet freedom. “Internet users must be granted the power to ward off undue intrusions into their personal lives by both the government and corporations.”

Over the past 12 months, false claims and hateful propaganda helped to incite jarring outbreaks of violence against ethnic and religious minorities in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, India, and Bangladesh. One of the steepest declines in internet freedom occurred in Sri Lanka, where authorities shut down social media platforms after rumors and disinformation sparked vigilante violence that predominantly targeted the Muslim minority. In India, internet users experienced an unprecedented number of shutdowns due in part to the spread of rumors on WhatsApp.

“Cutting off internet service is a draconian response, particularly at a time when citizens may need it the most, whether to dispel rumors, check in with loved ones, or avoid dangerous areas,” Shahbaz said. “While deliberately falsified content is a genuine problem, some governments are increasingly using ‘fake news’ as a pretense to consolidate their control over information and suppress dissent.”

In Egypt, a Lebanese tourist was sentenced to eight years in prison for “deliberately broadcasting false rumors” after she posted a Facebook video describing the sexual harassment she experienced while visiting Cairo. In Rwanda, blogger Joseph Nkusi was sentenced to 10 years in prison for inciting civil disobedience and spreading rumors, having questioned the state’s narrative of the 1994 genocide and criticized the lack of political freedom in the country.

“Populist and antidemocratic leaders are willfully eroding public trust in online information, asserting that fact-based accounts, personal opinions, and wholly fabricated reports should all be considered ‘fake news’ if they are critical of the government,” Shahbaz added. “If leaders are able to politicize the basic concept of facts, governments could avoid responsibility for their abuses and failures.”

Key findings:

- Declines outnumber gains for the eighth consecutive year: Since June 2017, 26 of the 65 countries assessed in Freedom on the Net have experienced a deterioration in internet freedom. The biggest score declines took place in Egypt and Sri Lanka, followed by Cambodia, Kenya, Nigeria, the Philippines, and Venezuela. Score declines in the Philippines and Kenya pushed those countries from a status of Free to Partly Free. Improvements were registered in 19 countries, with Armenia and the Gambia earning upgrades in their overall internet freedom status.

- China trains the world in digital authoritarianism: Chinese officials have held trainings and seminars on new media or information management with representatives from 36 out of the 65 countries assessed by Freedom on the Net.

- Internet freedom declines in the United States: The Federal Communications Commission repealed rules that guaranteed net neutrality, the principle that service providers should not prioritize internet traffic based on its type, source, or destination. In a blow to civil rights and privacy advocates, Congress reauthorized the FISA Amendments Act, including the controversial Section 702, thereby missing an opportunity to reform surveillance powers. Despite an online environment that remains vibrant, diverse, and free, disinformation and hyperpartisan content continued to be of pressing concern.

- Citing fake news, governments curb online dissent: At least 17 countries approved or proposed laws that would restrict online media in the name of fighting “fake news” and online manipulation. Thirteen countries prosecuted citizens for spreading allegedly false information.

- Authorities demand control over personal data: Governments in 18 countries have increased state surveillance since June 2017, often eschewing independent oversight and weakening encryption in order to gain unfettered access to data. At least 15 countries considered data protection laws over the past year, including misguided attempts to protect citizens by simply requiring that their data be stored locally, without enshrining protections against improper government intrusion.

- More governments manipulate social media content: In 32 out of 65 countries, progovernment commentators, bots, or trolls manipulated online discussions and content. This practice has become significantly more widespread and technically sophisticated in recent years, often moving from open platforms like Facebook and Twitter to closed messaging apps such as WhatsApp, where it may be more difficult to address.

- Internet freedom declines coincided with elections: In almost half of the 26 countries where internet freedom declined, the reductions were related to elections. Twelve countries suffered from a rise in disinformation, censorship, technical attacks, and arrests of government critics in the lead-up to elections. As Venezuela held a presidential election in May, the government enacted a vaguely written law that imposed severe prison sentences for inciting “hatred” online. Ahead of Cambodia’s general elections in July 2018, there was a surge in arrests and prison sentences for online speech.

- Governments disrupted internet services for political and security reasons: Internet users in 22 countries experienced blocking of at least one social media or communication platform. In 13 countries, governments deliberately disrupted internet or mobile phone networks. Both Russia and Iran sought to block Telegram, while users in India experienced more internet shutdowns than their counterparts in any other country.

- Digital activism fuels political, economic, and social change: The internet continues to serve as a tool for democratic change. Armenia rose from Partly Free to Free after citizens effectively used social media platforms, communication apps, and live-streaming services to bring about the country’s Velvet Revolution in April. Internet freedom improved in Ethiopia after its new prime minister released prominent bloggers and activists from prison and promised to reduce the country’s tight online restrictions.

To view the report, visit www.freedomonthenet.org.

Freedom House is an independent watchdog organization that supports democratic change, monitors the status of freedom around the world, and advocates for democracy and human rights.